Now, we’re finally reaching the point where the block-cipher stuff gets really fun: block cryptanalysis.

As I’ve explained before, the key properties of a really good

encryption system are:

- It’s easy to compute the ciphertext given the plaintext and the key;

- It’s easy to compute the plaintext given the ciphertext and the key;

- It’s hard to compute the plaintext given the ciphertext

but not the key; - It’s hard to compute the key.

That last property is actually a bit of a weasel. There are really a wide variety of attacks that try to crack an encryption

system – meaning, basically, to discover the key. What makes that

statement of the property so weasely is that it omits the information available to the person trying to crack it. In the first three properties, I clearly stated what information you had available to produce a result. In the last, I didn’t.

There’s a reason that I weaseled that. Partly, it’s because a correct statement of it would be ridiculously long and incomprehensible; and partly because it’s often deliberately set up differently for different encryption systems. You can design systems that are extremely strong against certain attacks, but not so good against others. There’s no universally ideal encryption system: it’s always a matter of tradeoffs, where you can handle some scenarios better than others.

Today we’re going to look at one particularly fascinating attack that’s used against block ciphers. It’s called differential cryptanalysis.

So what is differential cryptanalysis? It’s a technique that looks at how making specific changes in the plaintext input to the cipher produce changes in the output from that cipher. The basic idea, in its simplest form, is that you’re able to select a collection of plaintexts, and encrypt them. Then based on the results of doing

that, you try to compute the key.

Differential cryptanalysis is a form of the basic chosen plaintext attack. What makes it a differential attack is that you use related families of plaintext. That is, you’ve got a family of texts T0, T1, T2, …, where each text Ti is equal to T0 plus some small difference. For many differential attacks, that small difference is one bit.

How can you crack a cipher this way? To start, we assume that you know what cipher we’re using. For example, you know that we’re using DES with a 56 bit key. So you take your initial plaintext,

T0, and you encrypt it, giving you a ciphertext, C0. Then you change one bit of T0, giving you T1, and you encrypt that, giving you C1.

C1 differs from C0 in some number of bits. Now, you’ve reduced the problem from “What key could produce the plaintext/ciphertext pair (T0, C0)?” to

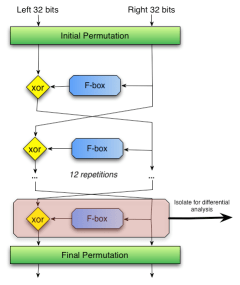

“What set of keys could produce the variation C0 to C1 by changing one bit of T0?”. I’ve drawn an outline of this process in a diagram to the right.

This reduction can be dramatic. For example, in one of the early proposal rivals to DES, caled FEAL, it turned out that you could crack it with a set of 8 one-block (plaintext,ciphertext) pairs. The problem is reduced from a blind search of a search-space of 264 possible keys to utter triviality by a set of 8 chosen plaintexts!

The subtlety of this attack is in how you choose the

set of plaintexts to use. For a typical Feistel network block

cipher, you need to do a very delicate analysis of the S-blocks. You trace out the possible paths of each bit through the network,

and using that, you can work out a set of probable differences – that is, bit patterns that are likely to be able to produce an informative difference in the ciphertexts. These probable patterns are called differential characteristics. Once you’ve worked out a large enough set of probably characteristics, you can use them to assemble a set of informative plaintexts that should provide you with what you need to determine the key.

It can get even more subtle than that. Since you know the algorithm, you can isolate a single stage of the cipher (as illustrated to the right), and throw bit-blocks at it in differential style. From that, you can work out the set of subkeys that could produce the observed differential result for that stage. If you do that for all of the stages, you’ll get a set of keys for each stage. Figure out which subkeys keys from each stage are mutually compatible, and then combine them, and you get a very small (usually one) key that could produce valid subkeys for each stage.

You can even repeat this process on multiple levels. If you’ve got a block cipher like DES, and you know the structure, you can do the differential analysis of a single stage by decomposing it into its individual S-boxes. Analyze each S-box, and come up with a set of potential subkey-fragments, and then combine those to create a set of potential subkeys for the stage. Then combine the stage results.

Differential analysis also reveals something fascinating about

DES. Most texts attribute the invention of this attack to Shamir in

the late 1980s, when he published a set of papers describing

differential attacks. But when you analyze DES, you find that it’s

not very susceptible to differential attacks! In fact, it

takes 255 chosen plaintexts to crack 56-bit DES – so differential analysis is effectively no better than simple brute force. But if you make some very minor changes to S-boxes in the algorithm, it becomes nearly as susceptible as FEAL.

So how is DES so resistant to an attack that wasn’t discovered

until almost 15 years after DES was first published? It turns out

that the IBM team that designed DES had figured out differential

attacks before they designed DES in 1974. They knew about that attack and its properties, and specifically designed DES to not be susceptible to it. But at the time, they were working with the NSA to produce an official standard encryption system, and the NSA requested that they not tell anyone about the attack they’d discovered.

This, naturally, has driven a lot of interesting discussion. Why did the NSA want to keep that secret? They claim that they did it because revealing the differential attack and how DES protected against it would “weaken the competitive advantage that the US enjoyed over other countries in the field of cryptography”. But

a lot of people (to be honest including me) believe that the real

advantage they wanted to maintain was the ability of the US

intelligence community to crack encryption systems used by other countries.

One last comment, and I’ll wrap up this post. Things like differential cryptanalysis are one of the many reasons not to roll your own cryptographic cipher. Some of the best cryptographers in the world – people who spent all of their time working on designing secure cryptosystems – designed systems that were easy to break using this technique. If you don’t know about every technique that could be used against your system, and you haven’t considered how your system will behave under probing by those techniques, then you have close to no chance of designing something unbreakable. Over time, so many cryptosystems have failed, because someone didn’t notice one tiny little problem, or didn’t think about one obscure technique, or didn’t notice one tiny little bug in their implementation. Those things are fatal to a good cryptosystem. Many of us who are math geeks have tried designing a cipher for the heck of it; how many of us who’ve done it are able to say that we’re sure that it couldn’t be cracked in five minutes of differential analysis? I’d wager that the answer is zero.

It is an interesting history of what the NSA wanted to keep secret. I remember when George Davida at Wisconsin-Milwaukee had a paper requested to be withdrawn about DES S boxes in the late 80’s. It seemed quite obscure.

The theory (i.e. WAG’s and speculation) back then was that DES had built in weaknesses from the NSA and it was fascinating when Don Coppersmaith et al started to talk about their design process and the fact that the NSA was fine with a strong version.

“In fact, it takes 2^55 chosen plaintexts to crack 56-bit DES – so differential analysis is effectively no better than simple brute force.”

I thought the differential attack was the reason why NSA recommended cutting the key length to 56 bits. Anything more was an overkill.

I don’t think that differential cryptanalysis is a type of chosen plaintext attack.

Chosen plaintext attacks require access to an oracle. You must be able to submit your chosen plaintexts to the encryptor and examine (compare) the ciphertexts. In other words, you must be able to interrogate the oracle.

However, if you have *only* ciphertexts, you still may very well carry out differential cryptanalysis. Perhaps it won’t get you the key, but you possibly will get near to the plaintexts.

Suppose you have a stream cipher, or a block cipher in OFB or CTR mode. The encrypting party is uneducated enough to encrypt two separate English (or other known-protocol) messages using the same IV. (There are examples for this in the industry.) Since both in OFB and CTR the ciphertext is produced by XOR-ing the plaintext with the plaintext-independent cipherblocks, by XOR-ing two ciphertexts, one XOR-s out the cipherblocks and ends up with the XOR of two English messages. Cryptographers break *that* in their sleep (letter and word frequency etc). This attack, although trivial, *is* differential cryptanalysis, because it’s based on the difference between ciphertexts. However, no encryption (chosen plaintext) takes place in this attack.

Mark, it’s usually not necessary to attack multiple rounds of a cipher. One round will suffice. For DES, if you find one round key (48 bits selected from the 56 key bits), you just brute-force the remaining 16 bits.

hmm… makes my Caesar cipher encryption look pretty weak. lol. Not that i use it for anything.

sean

Nate:

My understanding (admittedly limited) is that for some ciphers, you can crack the key much faster by analyzing multiple phases and intersecting the compatible results – I don’t have my texts handy (they’re at home, and I’m at work), but I recall one example (FEAT-128 rings a bell?) where you could reduce the amount of brute-force work by more than an order of magnitude – from brute-force testing 64,000 keys to brute-force testing 1000 keys.

It’s another of those tradeoffs: is it faster to do the differential analysis on another round of the cipher, or to do a brute force using what you know?

There seem to be two contradictory stories about how DES became resistant to differential cryptanalysis.

Once upon a time, what “everyone knew” was: IBM sent their design to the NSA, who sent it back with mysteriously altered S-boxes, and it later transpired that what NSA had done was to make the design resistant to differential cryptanalysis. (Alan Konheim: “We sent the S-boxes off to Washington. They came back and were all different.”)

But now the common wisdom is apparently that really IBM knew about differential cryptanalysis too (they called it the “tickle attack”) and the NSA didn’t change anything. (Walter Tuchman: “We developed the DES algorithm entirely within IBM using IBMers. The NSA did not dictate a single wire!”)

I don’t see how these can both be correct, or even both be good approximations to the truth; either the S-boxes went off to Washington and came back all different, or they didn’t.

The “new” story seems to be a little better supported by evidence, but it’s pretty thin.

Anyone know the real history here? (The various accounts on the web seem unhelpful; they quote one story, or the other, or quote both but notice no tension between them. Perhaps I’ve missed one that resolves the issue.)

Great thanks for dicrovering the topic.

I’m also confused on the history of the DES s-boxes, for the exact same reasons “g” cited just above.

Anyone know of any good sources on this? We seem to have two mutually exclusive stories being circulated.

is that we call Tickling attack???